Controlling the Media in Iraq

As an online special, we’re making this article available in its entirety. You may choose to read either the html version or a PDF version.

In 2003, nearly 600 journalists working for news agencies from around the world traveled alongside U.S. and coalition forces as they invaded Iraq. The Pentagon’s embedded journalists program allowed reporters for the first time to attach themselves to military units. While Bush Administration officials hailed it for its intimate access to soldiers’ lives, media watchdogs criticized its often restrictive nature and publicly worried reporters would do little more than serve up rosy stories about soldiers’ courage and homesickness.

Critics also argued the embedding program was essential to the administration’s attempt to build popular support for the war in Iraq. Several influential members of the Pentagon leadership and the administration believed the media contributed to defeat in the Vietnam War by demoralizing the American public with coverage of atrocities and seemingly futile guerilla warfare. They hoped to avoid a similar result in Iraq by limiting journalists’ coverage of darker stories on combat, the deaths of Iraqi civilians, and property damage. As media commentator Marvin Kalb noted, the embedding program was “part of the massive, White House-run strategy to sell…the American mission in this war.”

While anecdotal examples of the worst excesses of embedded reporters abound, only a few studies have systematically considered news coverage by embedded reporters. Those studies show the program provided reporters with an insider’s view of the military experience, but also essentially blocked them from providing much coverage of the Iraqi experience of the war.

By examining the content of articles rather than the tone, and comparing embedded and non-embedded journalists’ articles, it becomes clear that the physical, and perhaps psychological, constraints of the embedding program dramatically inhibited a journalist’s ability to cover civilians’ war experiences. While most embedded reporters didn’t shy away from describing the horrors of war, the structural conditions of the embedded program kept them focused on the horrors facing the troops, rather than upon the thousands of Iraqis who died.

By comparison, independent reporters who were free to roam successfully interviewed coalition soldiers and Iraqi civilians alike, covering both the major events of the war and the human-interest stories of civilians.

But given the far greater frequency and prominence of published articles penned by embedded journalists, ultimately the embedding program proved a victory for the armed services in the historical tug-of-war between the press and military over journalistic freedom during war time.

war reporting in perspective

From the Pentagon’s perspective, the embedding program represented a potential compromise in a long-standing conflict between the press and the military over journalistic freedoms in a war zone. In the past 150 years, with the growth of both contemporary warfare and the modern media apparatus, the armed forces and the press have often been at odds in a battle to control information dissemination.

While accounts of warfare go back as far as cave paintings, most war historians mark William Howard Russell, an Irish special correspondent for the London Times, as the first modern war reporter.  In 1853, Russell was dispatched to Malta to cover English support for Russian troops in the Crimean War. His first-hand reports from the front lines, often criticizing British military leadership, were unique at the time and stirred up much controversy back in England, both rallying support from some quarters and scandalizing military leaders and the royal family. Bending under political pressure, the Times agreed to a degree of self-censorship, but a precedent had been set and news consumers would continue to expect the same caliber of war coverage in the future.

In 1853, Russell was dispatched to Malta to cover English support for Russian troops in the Crimean War. His first-hand reports from the front lines, often criticizing British military leadership, were unique at the time and stirred up much controversy back in England, both rallying support from some quarters and scandalizing military leaders and the royal family. Bending under political pressure, the Times agreed to a degree of self-censorship, but a precedent had been set and news consumers would continue to expect the same caliber of war coverage in the future.

Since Russell’s time, the relationship between the media and military has undergone many transformations. During World War II, American military and political leaders carefully noted the morally reprehensible yet highly effective propaganda of the Nazi party, most notably Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. They responded with their own propaganda series, Why We Fight, created through the combined talents of director Frank Capra and Disney’s animation staff.

In terms of frontline coverage, the United States military exercised limited censorship with a largely cooperative and nationalistic press, yielding what military scholar Brendan McLane called, “from the military perspective…a golden age of war reporting.” Even independently minded reporter Edward R. Murrow, later a hero to many journalists for his bold castigation of the McCarthy hearings, provided assurances of the moral righteousness of the American military campaign alongside vivid descriptions of Allied bombing raids.

By contrast, the low levels of censorship, convenient transportation, and the significant technological advancement of television made coverage of the conflict in Vietnam the ideal of war coverage for much of the press. Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration policy of “minimum candor” with the press as well as the military’s efforts to push only those stories that emphasized progress led to the widespread belief in a “credibility gap” between what government officials claimed and the reality of the situation.

However, even if military and political leaders were successful in obstructing journalists in the White House press room, the very nature of a guerilla conflict with an ever-shifting frontline gave journalists in Vietnam excellent access to soldiers and civilians alike. In addition, with the advent of television and advancements in the portability of TV cameras, reporters were able to transmit powerful images of the conflict into living rooms, censored only by editors’ sense of propriety and Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulations.

While collective memory of the journalism during the Vietnam War today tends to be of the courageous release of The Pentagon Papers by New York Times reporters or the image of the free-roaming photojournalist played by Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now, it’s worth noting that, for more than 10 years until the late 1960s, the majority of the press corps complacently accepted the official story. Nonetheless, the important distinction between the modes of war reporting in World War II and Vietnam is that war correspondents in Vietnam—David Halberstam, Stanley Karnow, and Peter Arnett among them—always had the opportunity to roam and report on the story they chose.

More than three decades later, it has become axiomatic that most military leaders and many among the political right believe a liberal-leaning press corps “lost” the Vietnam War by demoralizing the public with horrific images and accounts of atrocities. And, indeed, this simmering resentment has made military-media relations since Vietnam incredibly tense. During the first Gulf War, the media furiously complained about the infamous “press pools” that forced journalists into parroting official press releases from military headquarters in Kuwait. On occasion, selected journalists were allowed to ride with military minders on a tour of the battlefield after the struggle had ended and the bodies were removed. In the mid-1990s, the military was left similarly fuming as journalists arrived in Somalia before the troops.

Pentagon leadership, well aware that an ongoing feud with the press was not in its best interests, formed two workgroups to study the issue of how better to manage the press in wartime. In 1984, under the leadership of Brigadier General Winant Sidle, a military panel was charged to examine how to conduct military operations while protecting military lives and the security of the operation but also keeping the American public informed through the media. In the wake of complaints about the Desert Storm press pools, military and media leaders met for the Pentagon-Media Conference in 1992 and agreed on several principles of news coverage in a combat zone.

In the intervening years prior to the embedding program, technological changes once again altered the nature of war reporting. As satellite phones became more portable journalists became more self-sufficient, able to coordinate with newsrooms and feed reports, images, and video instantaneously. The newfound capacity of journalists to transmit information on the spot presented a new set of threats to operational security. Without the traditional lag-time of war reporting, even well-intentioned journalists might accidentally reveal information of strategic significance, such as locations or troop levels. Based on the recommendations of the various workgroups and the practical consequences of technological innovation, Pentagon officials began to develop training programs and other provisions for embedding in the next major conflict.

into the fray

In 2002, as the specter of conflict with Iraq began to loom larger, Pentagon officials announced a week-long “Embed Boot Camp” for journalists hoping to participate in the program. Reporters were outfitted with Kevlar helmets and military garb, slept in barracks bunks, and ate military grub in the mess hall aboard the USS Iwo Jima. Marines trained them in military jargon, tactical marches, direct fire, nuclear-biological-chemical attacks, and combat first aid.

Perhaps more significantly, embedded reporters were forced to sign a contract and agree to the “ground rules”—allow their reports to be reviewed by military officials prior to release, to be escorted at all times by military personnel, and to allow the government to dismiss them at any time for any reason.

Before a single word was printed, many speculated that embedded reporters would fall victim to Stockholm Syndrome, the condition, named after a notorious 1973 incident in the Swedish city, in which hostages begin to identify with their captors. Media commentators like Andrew Jacobs at The New York Times, Richard Leiby at The Washington Post, and Carol Brightman at The Nation argued that as embedded journalists became socialized into military culture, they would develop relationships with the soldiers and start reporting from the military point of view.

While labeling this condition Stockholm Syndrome is perhaps slightly inflammatory, much sociological research suggests socialization is one of the military’s greatest strengths. In his classic collection of essays, Asylums, Erving Goffman noted the military is a total institution that not only controls all an individual’s activities, but also informs the construction of identity and relationships. In total institutions, such as the military, prison, or mental institutions, Goffman argued, the individual must go through a process of mortification that undercuts the individual’s civilian identity and constructs a new identity as a member of the institution. In such a communal culture, individuality is constantly repressed in the name of the institution’s larger values and goals.

In the case of embedded journalists, it’s easy to imagine how they might have come to identify with the military mission or, at the very least, the other members of their units. In addition to wearing military-issue camouflage uniforms, embedded journalists had to share living and sleeping space as well as food and water with their units. If embedded reporters ended up telling the story of the war from the soldiers’ point of view, as so many critics charged, it would simply be the natural and expected result of a process of re-socialization.

However, a different, and arguably more compelling, explanation exists for why embedded reporters might depict the war in a military-centric manner: they didn’t have the freedom to roam. George C. Wilson, for example, embedded for National Journal, compared it to being the second dog on a dogsled team, writing, “You see and hear a lot of the dog directly in front of you, and you see what is passing by on the left and right, but you cannot get out of the traces to explore intriguing sights you pass, without losing your spot on the moving team.”

Many sociological studies have observed that journalists, whether reporting from a newsroom in New York or a bunker in Baghdad, encounter what Mark Fishman has called a “bureaucratically constructed universe.” The constraints of journalists’ “universes” lead them to make certain assumptions, engage in specific practices, and only pursue particular types of stories. For example, a typical beat reporter is constrained by technical requirements such as word counts, the publication’s ideological commitments, and professional ideas about what is and isn’t newsworthy.

Several commentators, notably Michael Massing in the New York Review of Books, argued that in addition to these common limitations, the embedding program made covering soldiers’ experiences easy, while covering the experiences of Iraqi civilians was difficult, if not impossible. From the Pentagon’s perspective, the ease of access to soldiers was the essential strength of the embedding program. As Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs Bryan Whitman told The Nation, “you get extremely deep, rich coverage of what’s going on in a particular unit.”

alternatives to embedding

Although the embedding program was the dominant form of reporting during the early days of Operation Iraqi Freedom, two alternatives did exist. Though slightly more expensive than embedding, some news organizations opted to station a reporter in Baghdad. These journalists bunkered down at the Sheraton Ishtar or the Palestine Hotel in central Baghdad and watched as the American “shock and awe” bombing raid wrought death and destruction on the city.

During the first few weeks of the war, many Baghdad- stationed journalists attended briefing sessions led by Iraqi government officials and were escorted on tours of the city by official Iraqi minders. As Saddam Hussein’s government collapsed, Baghdad-stationed reporters took to the streets to cover the conflict and its consequences, either alone or with hired bodyguards.

The second alternative—funding an independent reporter with the freedom to roam—was far more costly and largely the province of elite news sources, particularly The New York Times and other national newspapers and wire services. In the weeks and months before the conflict began, many of these independent reporters traveled through Iran or Turkey into Iraqi Kurdistan and followed the slow advance of Kurdish forces and U.S. Special Forces toward Kirkuk and Mosul. Other independent reporters, after hiring a four-wheel-drive vehicle and private security team, fanned out across the country, often buckling down in potential battlegrounds like Fallujah and Basrah. While ground commanders interacted positively with independent reporters, on several occasions Pentagon officials criticized what they called “four-wheel-drive” and “cowboy” journalists for operating outside of the embedding program.

Like the embedded reporters, the other two arrangements for reporting from Iraq—being stationed in Baghdad or independent—represent distinct journalistic social locations (often defined in sociology as sets of rules, expectations, and relations based on status) that channeled journalists toward producing certain types of content and limited access to other types.

While embedded reporters had nearly unlimited access to coalition soldiers, Baghdad-stationed reporters would seem to have the most extensive access to Iraqi civilians. Although media accounts have suggested both embedded and Baghdad-stationed reporters presented a narrow view of the war, we would expect independent reporters, with the freedom and resources to roam at will were the least constrained of the three types of journalists, and, therefore, most likely to produce articles that balanced the Iraqi and the military experiences of the war.

Nonetheless, given that embedded reporting was the dominant form of reporting from Iraq (both in sheer numbers and in prominence), if the claims regarding embedding are true, then the vast majority of the news coming out of Iraq may have emphasized military successes and the heroics of soldiers, rather than the consequences of the invasion for the Iraqi people.

the embedding effect

Much of the existing systematic research on the embedding program has focused on the issue of rhetorical tone. Adopting an approach similar to the Stockholm Syndrome explanation, these researchers have argued that embedded reporters tend to sympathize with the soldiers they cover and adopt a more supportive tone when describing the mission in Iraq.

For example, a 2005 cross-cultural study of various network and cable television news programs found 9 percent of embedded reporters adopted a supportive tone as opposed to only 5.6 percent of “unilateral” reporters. Another 2006 study of 452 articles from American national daily newspapers found that compared to non-embedded reporters, embedded reporters produced coverage significantly more positive about the military and “implied a greater trust toward military personnel.” Research by the same group of scholars found similar results in broadcast news. These studies clearly suggest the embedding program encourages journalists to adopt a positive outlook on both the soldiers with whom they live and the military mission as a whole.

While these findings tell us much about the social psychological consequences of embedding, without considering the actual content of news reports it’s difficult to answer the more sociological question of how the various journalistic social locations inhibited or enabled journalists’ access to various types of stories. The only research to address the substantive content of embedded reporting is a 2004 Project for Excellence in Journalism (PEJ) study that examined 108 embedded reports from 10 different television programs. Among the results, PEJ found 61 percent of reports were live and unedited, 21.3 percent showed weapons fired, and combat was the most commonly discussed topic, covered in 41 percent of stories. Unfortunately, the PEJ study didn’t incorporate a comparison group of non-embedded journalists. Without such a group, we can’t compare the effects of various journalistic contexts on cultural production.

A study of the substantive content produced by embedded reporters and both types of non-embedded reporters would allow us to consider two questions of considerable sociological interest. First, we can better understand how institutional contexts in a war zone can shape the ability of journalists to report on various types of stories (or speak to varying types of people). By contrast, while a study of tone can tell us about how context shapes affective dispositions and/or ideological commitments, it does little to answer more concerning questions of limitations of access. Second, by focusing on content rather than tone, we learn more about what kind of information news consumers received. The capacity of governments to influence the types of information citizens have access to is an enduring theme of sociology, harking back to preeminent social thinkers from Karl Marx to C. Wright Mills.

a soldier’s eye view

To consider how the context of the embedding program may have limited journalists’ access and, thus, information about the war to the wider public, two research assistants and I studied five articles by each of the English-language print reporters in Iraq during the first six weeks of the war. We coded 742 articles by 156 journalists for five types of news coverage representing the soldier’s experience of the war and five types representing the Iraqi civilians’ experience. By comparing the differences in news coverage among embedded, independent, and Baghdad-stationed journalists, we are better able to understand how these different journalistic social locations may have limited reporters’ ability to present a balanced portrayal of the war.

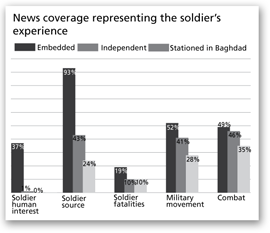

To capture the extent to which journalists depicted the soldier’s experience in Iraq, we recorded the frequency of news coverage of combat, military movement, soldier fatalities, the use of a soldier as a source, and the inclusion of a soldier human interest story (above, left).  As the results dramatically demonstrate, embedded reporters provided the most extensive coverage in all five categories representing the soldier’s experience of the war. Such thorough coverage of military happenings is perhaps unsurprising, considering embedded journalists used a soldier as a source in 93 percent of all articles, more than twice as frequently as independent journalists.

As the results dramatically demonstrate, embedded reporters provided the most extensive coverage in all five categories representing the soldier’s experience of the war. Such thorough coverage of military happenings is perhaps unsurprising, considering embedded journalists used a soldier as a source in 93 percent of all articles, more than twice as frequently as independent journalists.

More remarkable in light of much of the criticism of the embedding program is the fact that embedded reporters wrote about technical and often gritty subjects like combat and military movement in about half the articles. Clearly the common claim that embedded reporters wrote only “fluff pieces” about homesick soldiers is patently false (although soldier human interest stories were fairly common, appearing in 37 percent of all articles by embedded reporters).

Nonetheless, it’s worth noting that Baghdad-stationed reporters, and in particular independent reporters, were fairly effective at portraying the military perspective of the war. Though both types of non-embedded reporters rarely covered soldier human interest stories, they both used soldiers as sources and covered combat and military movement in a quarter or more of the articles. In fact, independent reporters covered the “hard facts” of the war (like combat and military movement) nearly as frequently as embedded reporters.

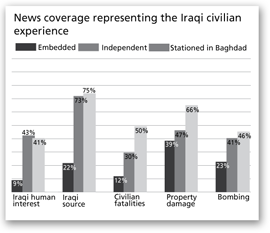

To document the extent of news coverage of the Iraqi civilian experience of the war, we noted the frequency of coverage of bombings, property damage, civilian fatalities, the use of an Iraqi civilian as a source, and the inclusion of an Iraqi human interest story (above, right).  The results show embedded reporters put forward a highly military-focused vision of the war, covering bombing and civilian fatalities and using Iraqis as a source far less frequently than either independents or reporters stationed in Baghdad.

The results show embedded reporters put forward a highly military-focused vision of the war, covering bombing and civilian fatalities and using Iraqis as a source far less frequently than either independents or reporters stationed in Baghdad.

Baghdad-stationed reporters provided the most extensive coverage of the consequences of the invasion, reporting on bombing, property damage, and/or civilian fatalities in half the articles. While independent reporters didn’t conduct all types of coverage as well as Baghdad-stationed reporters, they used an Iraqi source in nearly three quarters of the articles and covered Iraqi human interest stories in 43 percent of their articles.

Most troubling of all the disparities among embedded, Baghdad-stationed, and independent journalists is in their respective coverage of civilian fatalities. While estimates of Iraqi civilian fatalities during this period of the war vary widely, at least 2,100 civilians died during the first six weeks of the invasion. Though civilian deaths were acknowledged in half the articles by Baghdad-stationed reporters and 30 percent of articles by independent reporters, only 12 percent of articles by embedded reporters noted the human toll of the war on the Iraqi people.

These findings strongly suggest the Pentagon’s embedding program—the dominant journalistic arrangement during the Iraq War—channeled reporters toward producing war coverage from the soldier’s point of view. While Baghdad-stationed reporters were similarly narrow in covering the Iraqi civilian experience of the war, independent reporters, who had freedom to roam and chose their sources and topics, produced the greatest balance between depicting the military and the Iraqi experience of the war.

Although the embedding program didn’t print only good news, it did tend to emphasize military successes while downplaying the war’s consequences. With upwards of 90 percent of articles by embeds using soldiers as a source, as long as the soldiers stayed positive, the story stayed positive. And thus, an administration that hoped to build support for the war by depicting it as a successful mission with limited costs was able to do so through the embed program and without some of the more heavy-handed propaganda efforts of Operation Desert Storm.

It’s important to remember the embedding program was the only officially sanctioned mode of reporting, so we can’t say the three arrangements for journalists painted a complete portrait of the war. A full 64 percent of print journalists in Iraq were embedded (the figure is even higher among TV journalists). In terms of visibility, the imbalance toward embedded coverage is even more striking—of the 186 articles in the sample that ultimately appeared on the front page of a newspaper, 71 percent were written by embedded reporters. Based on the content of articles by embedded journalists and the overwhelming dominance of the embedding program, it seems clear that, in the aggregate, the majority of the news coverage of the war was skewed toward the soldier’s experience and failed to fully recognize the extent of the human and material costs.

embedding, then and now

Shortly after President George W. Bush declared an end to “major combat” in Iraq in 2003, most embedding terms came to an end. For a time, Iraq was considered safe enough by most western media outlets that journalists rented houses in Baghdad or freely traveled throughout the country. By September 2006 only 11 journalists were embedded with units in Iraq. However, as insurgent resistance grew many were forced to retreat to the safety of hotels protected by blast walls, occasionally taking excursions in armored cars with Iraqi bodyguards.

Today, a variation on the original embedding program exists, with journalists “embedding” with units on a particular mission or for shorter periods of time. Even journalists committed to depicting the Iraqi experience of the ongoing conflict, such as Jon Lee Anderson of The New Yorker, have traveled on brief stints with Army units because it’s one of the least dangerous ways to cover the insurgency.

At the same time, the rules of the embedding contract have become more restrictive. In June 2007, The New York Times reported that embedded reporters would now be required to obtain signatures of consent before mentioning the names of soldiers used in moving or still images as well as in audio recordings. Some journalists have contended the new rules further enhance the military’s ability to limit the release of undesirable news.

In the case of a future large-scale invasion (in Iran or Somalia, for example), both Pentagon officials and media industry leaders have indicated an interest in reviving the full embedding program. Should this happen, both sides must reconsider the nature of the embedding program, given its well documented pattern of leading journalists to produce reports that present the military in a more positive and less objective light.

recommended resources

Jon Lee Anderson. The Fall of Baghdad (Penguin Press, 2004). A beautifully written and vivid portrait of the first six weeks of the war by a Baghdad-stationed reporter.

Department of Defense. “Pentagon Embedding Agreement”, February 23, 2003. The contract journalists must sign before embedding with a military unit.

CFLCC Ground Rules Agreement: the list of rules for embedded journalists.

Department of Defense. “CJCS Media-Military Relations Panel (Sidle Panel)” August 23, 1984. The report of the findings of the Sidle Panel, which led to the development of the embedding program.

Mark Fishman. Manufacturing the News (University of Texas Press, 1980). An excellent sociological account of the journalistic process.

Andrew Jacobs. “My Week At Embed Boot Camp,” The New York Times Magazine February 3, 2003. A fascinating description of the activities at embed boot camp and the enthusiasm of military officials and journalists alike about the program.

Comments 7

ThickCulture » secrecy and transparency

February 27, 2009[...] the increased enforcement of the ban on such images marked a reversal of a larger trend. I have written elsewhere about the history of media-military relations, but, in short, military officials felt that journalists had far too much free reign in the [...]

schmedlap

April 4, 2009Much of the discussion and data in this article looks at the reporting in terms of reporting about Soldiers versus reporting about civilians. Just because a news story features civilians, that does not mean that it is any more or less truthful or objective than a story featuring Soldiers.

As for the embedding process, obviously Soldiers are far more accessible if you work among them. But was this program intended to force reporters into close proximity with Soldiers or did the media jump at this program in order to obtain that close proximity? I think it is clearly the latter. If there is an invasion going on, which story do you think interests people more: stories about our Soldiers or stories about civilians? This is an editorial decision. News outlets stay in business by selling advertising space. If nobody watches the program or reads the print, then the advertising space is not worth much. In order to get people to keep reading/watching/buying, they need to present news that interests people.

Among the “independent reporters” many were independent specifically because they would not find what they were looking for if they were in the vicinity of Soldiers – regardless of the conditions of the embedding program. So, again, it is an editorial decision, not an unfortunate by-product of the embedding process that the news outlets were snookered into.

Much of the reporting of so-called “independent reporters” was also not very independent. They were often played like fiddles by the various insurgent factions. Sadr’s militia and IAI were notorious for not just fielding their own “reporters” but for also feeding bogus news stories to independent reporters and otherwise reputable news outlets such as AP and (especially) Reuters.

“By examining the content of articles rather than the tone, and comparing embedded and non-embedded journalists’ articles, it becomes clear that the physical, and perhaps psychological, constraints of the embedding program dramatically inhibited a journalist’s ability to cover civilians’ war experiences.”

Is the assumption here that if a news story is scandalous then it is objective, but if it is consistent with some administration talking point then it was tainted by the embedding process?

“But given the far greater frequency and prominence of published articles penned by embedded journalists, ultimately the embedding program proved a victory for the armed services in the historical tug-of-war between the press and military over journalistic freedom during war time.”

Even if true, it was not a very decisive victory. We lost the information war among the American audience, hands down. Abu Ghraib. Haditha. Fallujah. All were propaganda windfalls for our adversaries in theater and a crushing blow to the war’s legitimacy at home, largely due to the media giving those stories greater importance and life spans than what they merited.

The hazards of embedded journalism « Down But Not Out

September 4, 2010[...] and publicly worried reporters would do little more than serve up rosy stories about soldiers’ courage and homesickness’. These fears proved to be grounded. Captain Victoria Wedgwood-Jones has stated that ‘the [...]

KCL

August 25, 2011Let me start by saying I am a Soldier and served 3 tours in Iraq and worked with media extensively. I think there are few things the author is overlooking in his research. 1st, why were the reporters there? Were they there to tell the story of the American Fighting Soldier the American reader or rather to tell the story of the war to the world? 2nd, you must consider the number of Iraqi media outlets. Prior to the war all media in the country was government controlled. There were only a handful of print and broadcast media outlets. I don't recall the exact number, but it was less than 15. After the fall of the government and the capture of Saddam, the number of media Iraqi outlets skyrocketed to more than 100. Why? Free speech. Those who could sustain, have sustained. 3rd, no news is completely neutral. No matter how much we like to fool ourselves, research shows we all have underlying reasons for writing or viewing events through a specific lens and portraying it in a certain light. 4th, why did reporters choose to embed (and it was a choice) why were the ground rule established? Safety and security. I can assure you getting shot at only looks cool in the movies. In reality, when bullets start flying and bombs are exploding, everyone looks for cover. Reporters sought the safety and security of the military for self preservation. There are numerous cases of journalists being shot, wounded even killed when operating as unilaterals. Additionally, numerous reporters conducted themselves in a manner placing themselves and military members in danger. (Geraldo Rivera's famous sand table map jumps to mind). 5th, and most obvious is the pay off. Not just financially, but for their careers. Every reporter was there by choice. None can say they weren't being extremely well compensated and that following in the footsteps of those who reported during the Vietnam War might not help advance their careers. Finally, might there not have been some sort group psychological effect. Not say the reporters were held captive, but as with any group, the longer you are with them, the more relate to their days, lives, struggle, etc.

Okay, that's my two cents for what it's worth.

andrew m. lindner

September 12, 2011kcl, thank you for your comments! I always appreciate hearing the perspectives of veterans who always have a much clearer sense of what happened on the ground than I do.

I also agree with your comments and don't see them as incompatible with what my findings. Indeed, as my research indicate, journalists reporting from Baghdad had as narrow a lens as embedded reporter, but from the civilian side of war. Most journalists chose to be embedded because it was more safe, the Pentagon preferred it, and they got great coverage from the inside of a military unit.

All reporters have subjective views and, at times, that can come on the page. It's an interesting topic, but outside the purview of my study.

Where I might disagree is the idea that the journalists are there to tell the story of the "American Fighting Soldier" or that they are even *supposed* to be there in the role of Americans citizens. In my view, the job of a journalist to try to represent the totality of the events as best as they can, attempting to capture as many people's experiences as possible. They also need to serve as a counter-balance to the power of all governments by seeking out any and all abuses of that power.

» One for the Status Quo MediaActivist

December 30, 2011[...] its lesson in marginalising media coverage of war. Gradually, reporters were kept at bay and into press pools, for their safety, we were [...]

The Embedded Tester « Manage to Test

April 12, 2012[...] and neglect, or leave out truths related to the enemy combatants. In fact, administrations have counted on this, encouraging embedding in order to provide more support for the war in [...]